On Wednesday evening the Leeds Animal Studies Network (https://leedsanimalstudiesnetwork.wordpress.com/) met for the latest installment of its seminar series. For those of us intrigued by animal history, the Network’s seminars have offered some great topics: from beagle colonies to the role of elephants in the timber industry of colonial Burma.

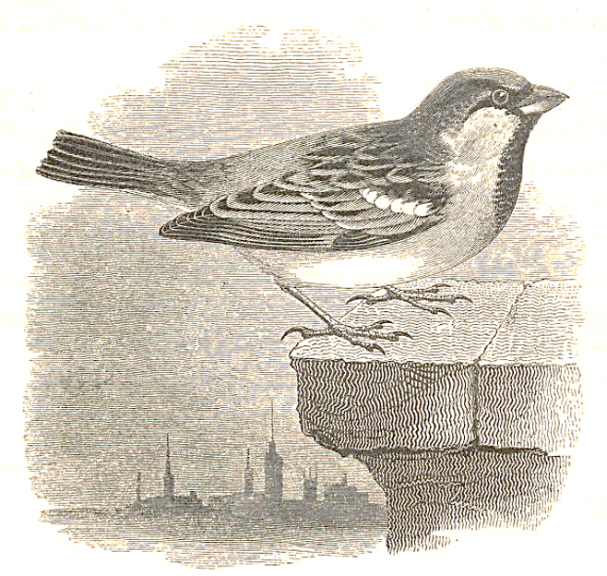

But the latest seminar featured my own (freshly published!) research on the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) in 19thc Britain. During this time, sparrows were generally perceived as “pests” or “vermin” which consumed farmer’s crops and damaged orchards. This attitude was summed up by the complaints of a farmer named Charles Newman, who wrote to his local newspaper in 1861 to protest against bird conservation. Newman, a self-proclaimed “practical farmer,” had little patience for those who wished to preserve sparrows:

“No doubt many persons are opposed to their [sparrows’] destruction, considering that this feathered race were created for some wise purpose. Such was undoubtedly the case in the original order. But the Great Creator made man to rule over the fowls of the air and the beasts of the field, leaving it to his judgment to destroy such that were found more destructive than beneficial.”

Newman was by no means alone in his hatred of sparrows, or as he termed them, “flying mice.” Arable farmers and horticulturalists regularly trapped, poisoned or shot sparrows on their land. Yet others thought that sparrows were not destructive, but useful. In 1862 the Royal Agricultural Society of England and Wales stated that insectivorous birds like sparrows consumed as much animal [insect] as vegetable matter, acting as ‘‘faithful protectors’’ of ‘‘cultivation in general.” Some naturalists feared that destroying sparrows would upset the delicate balance of nature. As early as 1841, a letter to The Quarterly Journal of Agriculture told the tale of a horticulturalist who had exterminated sparrows in his fruit orchard, only to suffer ‘‘myriads of caterpillars, green and black-marked ugly things,’’ which stripped whole bushes of their leaves.

The idea of using sparrows as a form of biological control against harmful insects was enacted across the globe. Sparrows were introduced to both Australia and the United States by acclimatisation societies during the 1860s. Yet attitudes towards the sparrow in both countries quickly turned sour. In 1878 an article in The Derby Mercury charted the rapid reversal of Australian opinion:

“For ten or fifteen years, perhaps, the Australian gardeners and farmers and the sparrows got on exceedingly well together. The busy little birds faithfully performed all that was expected of them, and the land was well nigh rid of grub and caterpillar. Presently, however, there gradually arose a feeling of uneasiness as to the increase and multiplication of the imported blessing.”

In the face of such failures, the acclimatisation movement declined. Natural history also suffered a decline during the latter half of the 19thc (https://holmesmatthew.wordpress.com/2015/11/25/the-decline-of-natural-history-rise-of-biology-in-19thc-britain/). Economic ornithology, described as ‘‘the study of the inter-relation of birds and agriculture’’ by the President of the Royal Agricultural Society in 1892, took over the issue of whether sparrows were harmful or beneficial for agriculture. British economic ornithologists followed the lead of their American counterparts by condemning sparrows for consuming cereal crops. Following the outbreak of the First World War, sparrows were therefore persecuted on a systematic basis.

If you’re interested in finding out more about the sparrow in 19thc Britain, or how matters of social and scientific consequence were decided during this time, my paper “The Sparrow Question: Social and Scientific Accord in Britain, 1850–1900” has just been published by the Journal of the History of Biology. It is Open Access and you can read or download it from the journal’s website at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10739-016-9455-6. Or you can read it and my other publications on my Academia page: http://leeds.academia.edu/MatthewHolmes.