Before “science” in its modern sense existed, denizens of early modern Europe sought to explain their world through a system of knowledge termed “natural philosophy.” Natural philosophy covered a diverse array of subjects, from theology to pharmacology to natural history. The collection of chapters in Knowing Nature in Modern Europe seek to examine some of these disciplines, their methodologies and practices, while bringing together approaches from humanistic Renaissance studies and the history and philosophy of science. The book is divided into three sections, each containing three case studies by different authors. A few notable examples from the fields of physiology and natural history spheres are covered below:

The Moral Physiology of Laughter – Stephen Pender.

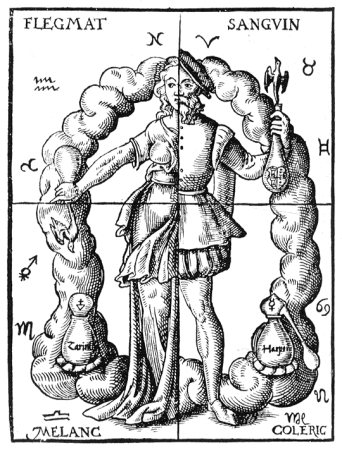

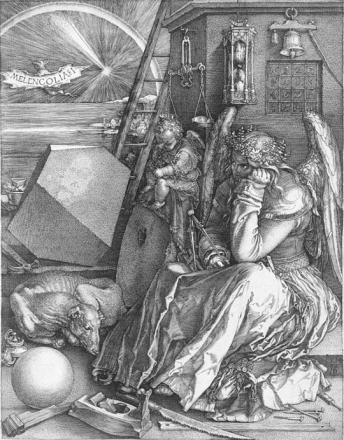

On the left, a medieval depiction of the four humors. On the right, Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I from 1514: http://publicdomainreview.org/2013/05/01/as-a-lute-out-of-tune-robert-burtons-melancholy/

Is laughter really good for you? According to some seventeenth-century writers, bouts of laughter were dangerous for body and soul. French physician Jean Fernel argued that, in cases of extreme merriment, death could result as “the Cordial Blood, and Vital Spirits, are… suddenly diffused to the exterior parts, that Life goeth out therewith, and returneth not.” Descartes tackled the physiological mechanisms behind laughter in The Passions of the Soul (1649), describing how a sudden rush of blood inflated the lungs to expel “an inarticulate and explosive cry.” Philosophy in his time was a “way of life,” with therapeutic applications for troubled minds. A key part of this lifestyle was rhetoric and conversation – or the art of knowing when laughter was appropriate. Moral aspects of laughter were therefore intertwined with its physiology.

The Use of Scripture in the Beast-Machine Controversy – Lloyd Strickland.

When Descartes carved up the universe between the corporeal and the spiritual in his Discourse on the Method (1637), animals became automatons, devoid of soul, or even mental activity. By the end of the eighteenth century, Descartes’s views on the beast-machine steadily lost popularity, in tandem with Cartesian philosophy. Strickland notes how actors in the controversy (including Descartes) readily claimed their philosophy acted in accordance with scripture. Supporters of animal automatism cited passages in Leviticus and Deuteronomy to declare that the blood, rather than a soul, drove animal action (which raised difficulties for animals with no blood). Ultimately, appeals to scripture from both sides were often corroboratory in nature, proving no more helpful in solving the controversy than empirical or rational arguments.

Early Modern Natural Science as an Agent for Change in Naturalist Painting: Jacopo Ligozzi’s Zoological Illustrations as a Case Study – Angelica Groom.

Ulisse Aldrovandi, watercolor of vol.002 Pets:

http://www.librari.beniculturali.it/opencms/opencms/it/comitati/comitati/comitato_1.html

In a lavishly illustrated piece, a ten-year (1577-87) collaboration between naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi and naturalist painter Jacopo Ligozzi at the Medici court is depicted. Ligozzi was charged with visually recording the flora and fauna of the grand ducal collections. At the time, natural objects were “improved” by artists through the aesthetic conventions of Florentine mannerisms. Zoological and botanical images were then passed between illustrators for copying, facilitating the movement of visual information around Europe. Prints from the Medici collection appeared in Aldrovandi’s work, who exercised a great degree of control over the production of natural history images, ensuring aesthetic convention did not trump accurate observation. Yet artists’ access to courtly menageries proved instrumental in the development of greater mimeticism in zoological paintings.

Knowing Nature in Modern Europe provides a series of intriguing insights into how nature was studied and interpreted in early modern Europe.

David Beck, (ed.), Knowing Nature in Early Modern Europe (London, Pickering & Chatto, 2015) is available in hardback and as an ebook (£24 incl. VAT for PDF, £20 excl. VAT for EPUB) at: http://www.pickeringchatto.com/titles/1806-9781848935181-knowing-nature-in-early-modern-europe